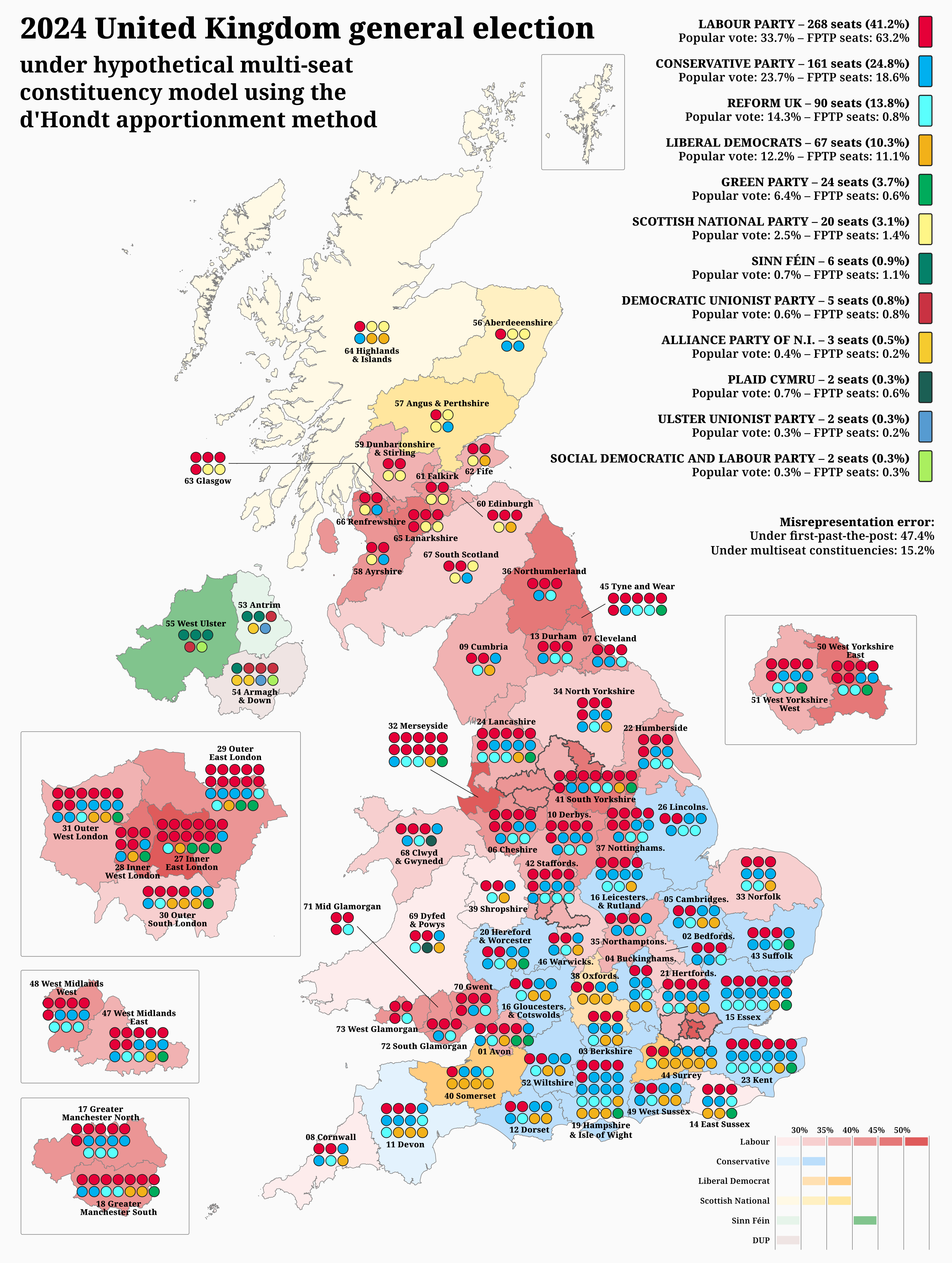

1. Drawing electoral boundaries

Electoral boundaries should try to follow existing cultural/administrative boundaries that British people are familiar with (their county, for example) as best as possible.

For the sake of it being the only available voting data, I combined existing FPTP constituencies to form the new ones.

They generally tend to follow county boundaries (which is good) but there are a few inconsistencies that arose when electoral boundaries were redrawn for the 2024 election

not always following county boundaries.

So for the purposes of this map we have Tiverton being lumped into Somerset, Bordon into Surrey, Malmesbury into Gloucestershire, Wetherby into North Yorkshire, and a couple

others.

2. Constituency size

One of my first observations upon working on this project is that the more seats a constituency has, the more closely allocated seats proportionally match popular vote

(an explanation as to why is under the

Critical analysis of results section), so larger constituencies are favourable for proportionality reasons.

However, as explained earlier, a larger constituency may detract from the local/regional representation aspect so the compromise I decided on is to limit the minimum

constituency size to 4 seats and the maximum to 20 seats (a 75-seat London constituency would be ridiculous, as would a 1-seat Shetland & Orkney constituency).

This meant that some big counties had to be split apart and some small ones combined with others.

- County Armagh (2 seats) — combined with County Down (6 seats) to form Armagh & Down

- County Derry/Londonderry, County Fermanagh, and County Tyrone — combined to form West Ulster

- Gwynedd (2 seats) — combined with Clwyd (5 seats) to form Dyfed & Powys

- Herefordshire (2 seats) — combined with Worcestershire (6 seats) to form Hereford & Worcester

- Isle of Wight (2 seats) — combined with Hampshire (18 seats) to form Hampshire & Isle of Wight

- Powys (2 seats) — combined with Dyfed (4 seats) to form Dyfed & Powys

- Rutland (0.5 seats) — already too small for one, combined with Leicestershire (10.5 seats) to form Leicestershire & Rutland

- Angus, Dundee, and Perth and Kinross — combined to form Angus & Perthshire

- Middle four constituencies of Scotland that make up Falkirk, West Lothian, and parts of Clackmannanshire — combined to form Forth as no other clean way to group them

- Argyll and Bute, Highlands, Orkney, Outer Hebrides, Moray, and Shetland — combined to form Highlands & Islands as no other clean way to group them

- Five southernmost constituencies of Scotland — combined to form South Scotland as no other clean way to group them

- Greater London (75 seats) — split following ONS International Territorial Level (previously EU NUTS-2) regions into

Inner London East (17 seats) covering Hackney, Haringey, Islington, Lambeth, Lewisham, Newham, Southwark, and Tower Hamlets;

Inner London West (9 seats) covering Camden, City of London, Hammersmith and Fulham, Kensington and Chelsea, Wandsworth, and Westminster;

Outer London East (19 seats) covering Barking and Dagenham, Bexley, Enfield, Greenwich, Havering, Redbridge, and Waltham Forest;

Outer London South (12 seats) covering Bromley, Croydon, Kingston upon Thames, Merton, and Sutton;

and Outer London West (18 seats) covering Barnet, Brent, Ealing, Harrow, Hillingdon, Hounslow, and Richmond upon Thames

- Greater Manchester (27 seats) — split into Greater Manchester North (13 seats) covering Bolton, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, and Wigan,

and Greater Manchester South (14 seats) covering Manchester, Salford, Stockport, Tameside, and Trafford

- West Midlands (26 seats) — split into West Midlands East (15 seats) covering Birmingham, Coventry, and Solihull,

and West Midlands West (11 seats) covering Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall, and Wolverhampton

- West Yorkshire (22 seats) — split into West Yorkshire East (11 seats) covering Leeds and Wakefield,

and West Yorkshire West (11 seats) covering Bradford, Calderdale, and Kirklees

3. Allocation of seats

The D'Hondt method of apportionment, also known as the Jefferson method or the greatest divisors method, works by assigning a quotient to each party before

each round of allocation, with the number of allocation rounds equal to the number of seats open.

The quotient is given by:

V = number of votes received, and s = number of seats currently allocated (initially 0)

\[

quotient = \frac{V}{s + 1}

\]

The quotients are initialised as the total vote tally.

In the first round, the first-ranked party gets allocated a seat and their quotient becomes half their vote count

In the second round, the party with the highest quotient gets allocated a seat. If this is the first-ranked party, their quotient becomes a third of their vote count.

If it is the second-ranked party, their quotient becomes half of their vote count.

Repeat the process until all seats have been filled.

This loop in Python looks like:

while total_seats < number_of_seats:

max_party = max(sorted_votes, key=sorted_votes.get)

seats[max_party] += 1

total_seats += 1

sorted_votes[max_party] = votes[max_party] / (seats[max_party] + 1)

Below is an example for Warwickshire, a 6-seat constituency: